The Past That Has Not Passed

Wilhelm Rothschild was born in 1859 in the city of Cannstatt, Germany. He was a religious Jew who, like his father, earned his living from selling cattle – a common profession at the time, but not considered respectable in the eyes of Jews who wished to integrate into broader German society.

Wilhelm managed his business with complete honesty and integrity, and he earned the respect and esteem of his clients, who valued him greatly. He never did anything that would disgrace himself or dishonor Judaism. Although he was not poor, he did not live a life of luxury, and he made sure to donate and provide food for those in need.

Wilhelm RothschildAt the age of 39, Wilhelm married Sophie, who was 10 years younger than him, in an arranged marriage.

Wilhelm and Sophie were well-known figures in the local Jewish community. They made a point of praying regularly at the synagogue, not only on holidays but also on evenings and Sabbaths. Whenever a quorum (minyan) was needed, Wilhelm always volunteered.

They fasted on Yom Kippur and observed most of the other religious traditions as well, including buying meat only from the local Jewish butcher, Mr. Buxbaum, and strictly avoiding pork and non-kosher products.

Wilhelm and Sophie had four children: Julius, Liddy, Kitty, and Gretel (Gretchen). Their mother Sophie passed away in 1923, shortly before the birth of her granddaughter – Sophie (from London, cousin of Grandfather) – who was named after her.

Several years later, Gretel, the youngest daughter who had managed the household, died at the age of 30 from meningitis. Kitty emigrated to Scotland, and Julius, the first in the family to leave Germany, emigrated to Uruguay.

Lidi was born in 1902 and grew up in a modest yet principled home. As the second child in the family, she was expected to start working after completing eight years of compulsory schooling. She succeeded quickly and found a position as a secretary and bookkeeper at the textile factory Guttmann-Merx.

There she met Julius Merx, who would later become her husband.

From left – Julius, Liddy, Sophie, and Walter — around 1930

Love at First Sight

When Julius was on temporary leave from military service in 1917, Liddy, then only 15 years old, fell in love with him instantly. When Julius returned to the army, they regularly exchanged warm and heartfelt letters, leaving no doubt that their bond had quickly become mutual love.

After the war ended, Liddy became Julius’s personal secretary, and from then on, it was only a matter of time until she reached a suitable age for marriage so that they could realize their love.

For Julius’s family, however, their love story was in no way welcomed news. Their great love faced strong opposition from the Merx family. Like many families of their social standing, the Merxes were outwardly liberal, but when it came to marriage with a girl from a lower social class (the daughter of a cattle dealer), all their liberalism vanished. Everyone, including Uncle Martin, who was usually open-minded and understanding, tried to prevent what they considered such a terrible mistake.

Julius was not deterred by the resistance of his mother, Babette and the rest of the family, and nonetheless asked Wilhelm, Liddy’s father, for her hand in marriage in the traditional way. The Rothschild family may even have seen this as a blessing — an opportunity for their daughter to rise to a higher social status. Wilhelm gave his consent, assuring his future son-in-law that “he would never have to support his family,” but also made it clear that “he could not provide a dowry.” (A dowry was essentially a “payment” given in money or gifts from the bride’s parents to the groom.)

With quiet determination, Julius insisted that Liddy was a worthy match — intelligent and beautiful. And indeed, there were not many unmarried young Jewish women like her left in the area. Despite the opposition, on March 30, 1922, the wedding ceremony took place. Liddy was ultimately accepted as an inseparable part of the Merx family.

Ironically, over the years, Liddy so fully absorbed the family’s values that when her son Walter wanted to marry Charlotte- a girl deemed “unsuitable,” she herself strongly opposed it, just as the family had once opposed her.

From left – Julius, Liddy, Sophie, Walter, and Michael. In the back – Grandma Babette and friends.

Liddy and Julius moved to the small town of Neuffen, where they began their life together. Because of a heart condition, Liddy did not particularly enjoy physical activity, but she tried to please her husband and joined him on outings, even attempting to learn skiing – although she did not enjoy the sport. When Sophie and Walter grew old enough to accompany their father on hikes, she was happy to stay at home with Michael, the youngest son.

Liddy was a complex woman – strict and critical toward her children, believing that too many compliments could be harmful. Yet her love was profound, and she expressed it in other ways – through her care for her husband, her devotion to the family, and the values she instilled in them.

Julius tended to keep his feelings to himself. Liddy, in contrast, expressed emotions, but in a different way. Praise and affection were spoken rarely and never in front of the children, while anger or disappointment were always expressed directly. In her view, excessive compliments only inflated a child’s self-esteem unnecessarily, while criticism and moderate discipline with boundaries truly helped make people better.

Her love for her husband, however, she expressed openly: the two never kissed or embraced in front of the children, but often held hands in public on their walks, never quarreled in front of the children, and shared a warm and cooperative relationship.

Walter, Liddy, and Sophie

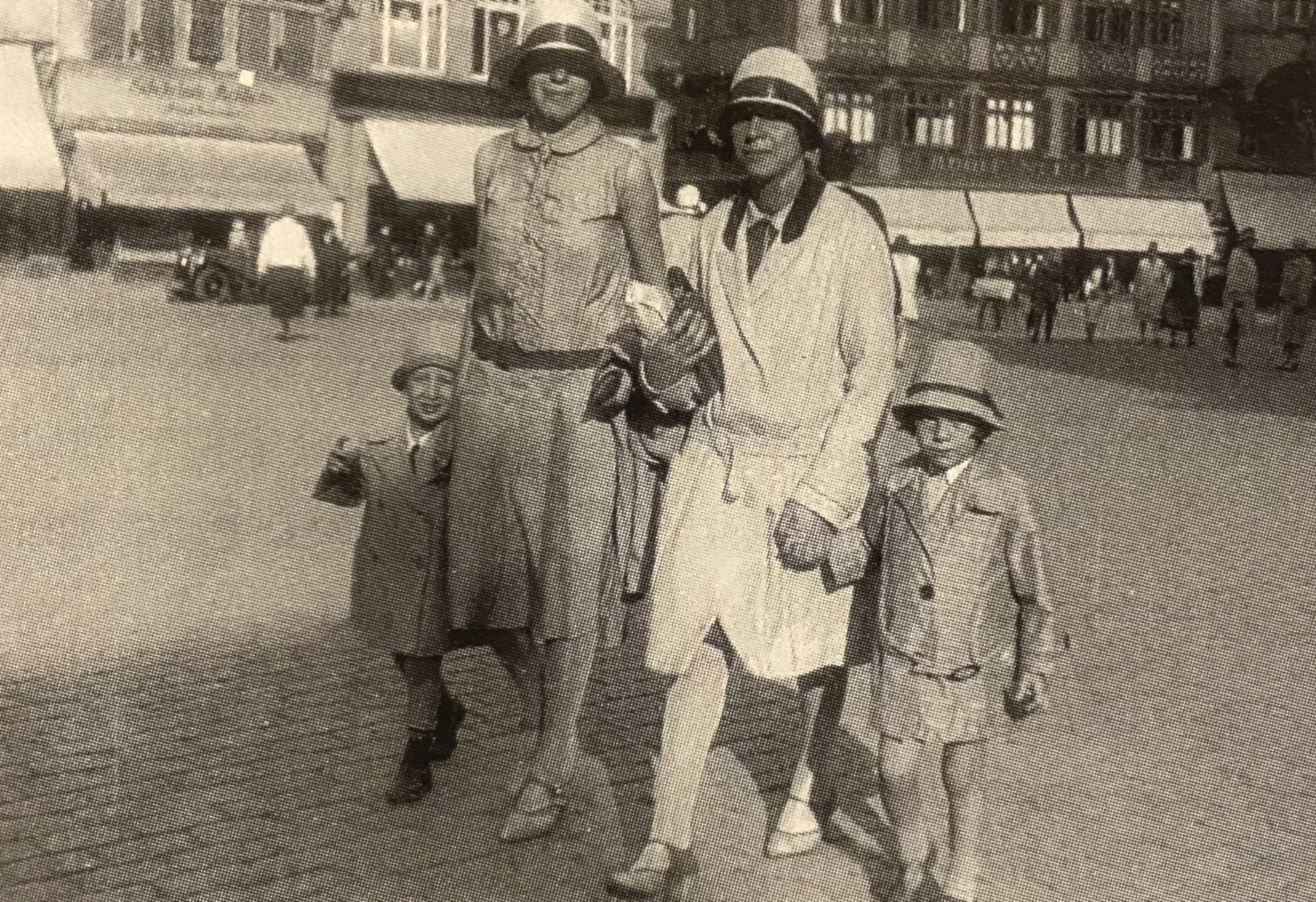

1929 – chic style! Walter and Sophie with their aunts, Kitty and Gretel

Grandfather Wilhelm Rothschild passed away at the age of 83. After the expulsion and persecution by the Nazis, his fate was known, but I will spare you the painful details. He remained alone in Cannstatt after his children and grandchildren had escaped in time.

Like many other elderly people, he was sent to the “well-known castle,” from which he never returned, and where he died that same year, 1942.

His son and grandson made sure to preserve the memory of a respectable and upright man. Despite his modest occupation, he brought great pride to his family. His name and memory have been preserved within the family – not only in stories, but also in the names of future generations.

Wilhelm 1940

The Last Letter

Points to Ponder

In the past, marriages were often arranged according to social class. Today, however, the criteria by which parents give their blessing to their children’s chosen partners are quite different, shaped more by values, aspirations, and personal compatibility than by rigid social standing.

Family names, too, tell a story. When the same names repeat themselves across generations, they carry with them not only personal histories but also a powerful message of continuity. Each name becomes a thread connecting past and present, linking one generation to the next.

Research shows that intergenerational trauma can reach back as far as fourteen generations. Patterns of thought, lingering anxieties, ways of expressing emotion, and even a sense of insecurity can be passed down to descendants who themselves never endured persecution. Issues of identity, belonging, and continuity are deeply intertwined with these invisible legacies.

Parenting styles also reflect this inheritance. Strictness, the need for control, and the demand for excellence can often be understood as survival mechanisms- ways parents sought to protect their children in uncertain and dangerous times.

Yet alongside the trauma, there exists remarkable resilience. Families also pass down spiritual strength, values, a sense of purpose, and inner fortitude. Faith, tradition, humor, family celebrations, and the strengthening of community ties form a parallel legacy, one that sustains and uplifts.

It is this combination- of resilience woven through trauma- that explains how the Jewish people have managed not only to survive, but to thrive and rebuild, time and again, despite all odds.